In early June 1916, the bodies of over sixty Royal Navy sailors were washed up on the west coast of Sweden. Many were wearing life jackets and many could be identified from the metal identity bracelets they wore. All were casualties of the most important naval battle of the First World War, the Battle of Jutland, when the British Grand and German High Seas fleets clashed in the North Sea off the coast of Denmark.

One of these bodies came ashore on the small island of Styrsö, south of Gothenburg, and was buried with full naval honours in the local churchyard. Swedish sailors and two hundred islanders attended the burial and many wreaths were placed on the grave. This was the grave of James Brown from Sunderland.

|

| Styrsö, from the sea, taken by Adbar, 2014, (via Wikimedia) Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike |

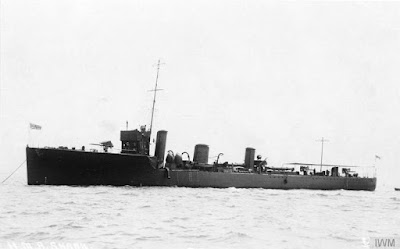

James had been born in Aberdeen in 1878. Later he moved to Sunderland and, in 1911, was working in Doxford’s shipyard and living in Hendon with his wife, Cecilia Ann, and three young children. On 15 March 1915, James joined the Royal Naval Reserve and, after training, was posted to Scapa Flow, the Grand Fleet’s main base at Orkney. There he joined HMS Shark as an Engine Room Artificer, helping to maintain the oil-fired turbine engines of this small, but fast, torpedo boat destroyer built by Swan Hunter in Wallsend in 1912.

The fighting at Jutland began late afternoon on 31 May and, within hours, two Royal Navy battlecruisers had exploded, killing over two thousand men. By early evening, as the main British battleships hunted the German fleet, Royal Navy destroyers, including HMS Shark commanded by Captain Loftus Jones, were ordered to attack. After firing one torpedo, Shark was hit by German shells and stopped dead in the water. The doomed destroyer was then pounded by German shells, but, before the destroyer sank, about one third of her ninety man crew clambered aboard two life rafts. Only six, however, were still alive, when they were found just after midnight by a Danish steamer. All the others had died from their wounds or the cold.

|

| HMS Shark, IWM non-commercial licence © IWM (Q 75119) |

Cecilia Brown was informed by the Admiralty of her husband’s death on 6 June 1916 and a brief account, under the heading ‘A Jutland Hero’, was printed in the Newcastle Journal on 20 July. In the early 1920s, Mrs Brown was given almost £70 by the Admiralty (worth about £3,500 today) as her husband’s share of the prize money for the German ships sunk at Jutland. She also received his three campaign medals.

In 1961, James Brown’s remains were moved by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission from Styrso, along with all the other Jutland casualties who had washed up on Swedish shores, and reburied in Kviberg Cemetery in Gothenburg. It is unlikely, however, that Cecilia Brown was ever able to visit her husband’s grave in Sweden.

Commander Loftus Jones, Shark’s captain, is also buried in Kviberg. In March 1917, he had been awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for his bravery and leadership at Jutland, despite being horrifically wounded. After the war, his widow was able to visit her husband’s grave and was there given the life belt that had been recovered from his body. That life belt is today in the Royal Navy Museum in Portsmouth, whilst his medals, including his VC, are in the Imperial War Museum. The whereabouts of James Brown’s medals are, however, unknown.

As for Jutland, despite the Royal Navy’s disastrous losses of men and ships and despite German claims of victory, the battle was not a British defeat. At Jutland, the German High Seas Fleet had failed to break the British blockade that was starving Germany of food and vital raw materials, and the Royal Navy’s control of the North Sea was never again challenged during the First World War.

No comments:

Post a Comment